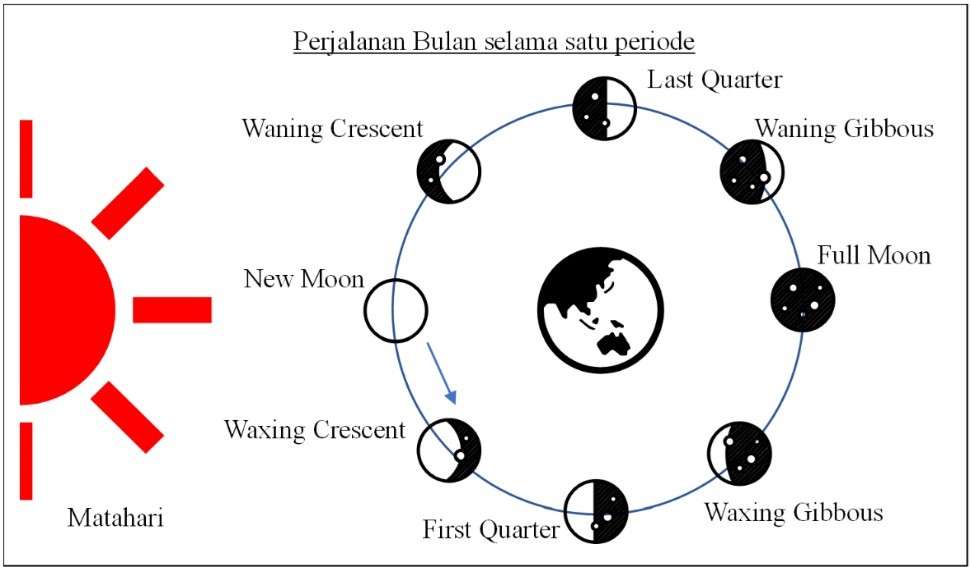

The phases of the Moon are formed independently of the Earth’s rotation on its axis. Even if the Earth were to stop rotating, as long as the Moon continues orbiting the Earth, the lunar phases would still occur. Thus, the lunar phases are, in essence, a global astronomical phenomenon. Meanwhile, the visibility of the crescent moon (hilal) is a local astronomical phenomenon, influenced by the Earth’s rotation. It is important to note that the visibility of the crescent is only concerned with the moment when the Moon (including the crescent) is above the horizon. This principle of crescent visibility is even further restricted, as a large crescent seen on the eastern horizon in the morning is not recognized as a hilal simply because it is not visible at the required time.

Meanwhile, the Islamic foundation given in Surah Yasin (36:39) and scientific principles teach that the final phase of the Moon (the last manzilah) must end at ijtima’ (conjunction). In science, ijtima’ is considered a dimensionless zero point. The implication is that, theoretically, even one second after ijtima’, the hilal (new crescent moon) has technically been born (exists), though it may not yet be visible. Since lunar phases are a global phenomenon, even when the hilal is below the horizon, it continues to grow because the Moon is constantly orbiting the Earth. The rate of change in the Moon’s phase strongly correlates with elongation changes and can be calculated simply based on the difference in the apparent angular speeds of the Sun and Moon, which appear to orbit Earth due to Earth’s rotation. The apparent angular speed of the Sun is around 15° per hour, while the Moon’s is approximately 14.5° per hour. Because of this angular speed difference, Surah Yasin (36:40) explains that the Sun cannot catch up to the Moon when the

‘urjūn al-qadīm (old crescent) forms. In other words, the moment of ijtima’, which concludes the final manzilah, also marks the end of the Moon’s synodic cycle. It is at this point that the Sun has caught up to the Moon, and the Moon’s phase at this position is the smallest in one synodic cycle. The implication is that after ijtima’, the Moon’s phase will start growing again as it enters the first manzilah in the next synodic cycle. This marks the first manzilah, when the hilal is formed. It is important to note that the Moon’s phase continuously increases from second to second solely due to the Moon’s orbit around the Earth— regardless of whether the hilal is above or below the horizon, and whether or not it is visible.

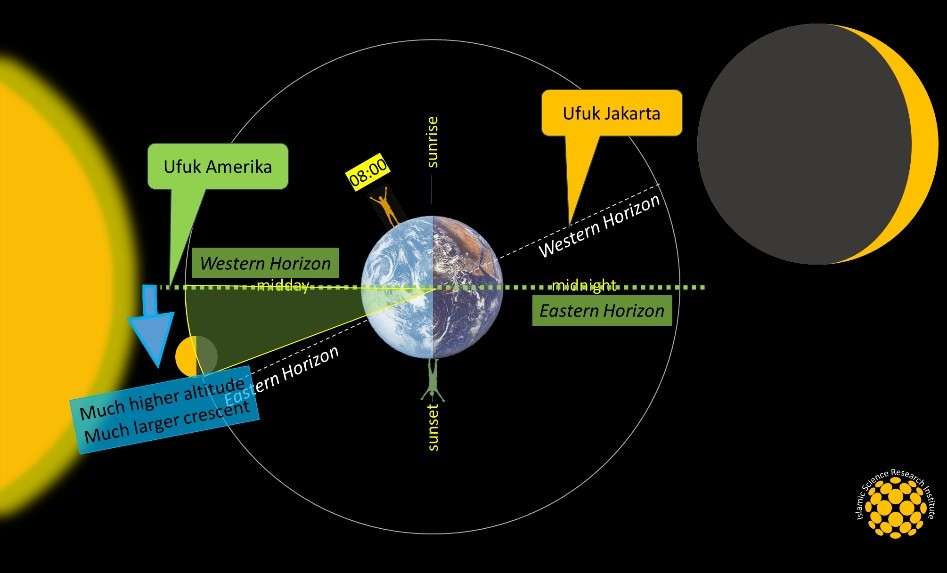

Figure-1 illustrates how the Moon’s phase continues to grow in Jakarta, even when it is below the local horizon. Around 2:00 AM (represented by the brown figure), the hilal (crescent) in relation to Jakarta’s horizon has become larger compared to sunset (Maghrib) approximately 8 hours earlier. This growth is due to an increase in elongation, calculated as: 8 hours × 0.5/ hour = 4. At this point, the hilal’s altitude is approximately -100° (negative altitude) measured against Jakarta’s western horizon. Meanwhile, at the same instant, in a location in Europe (represented by the green figure), it is Maghrib there. At sunset in Europe, the hilal’s altitude is around 4° higher than its altitude at Maghrib in Jakarta. This discrepancy arises because the elongation in Europe is greater due to Maghrib occurring about 8 hours later than in Jakarta. The issue is that while the hilal is recognized in Europe because it is visible (altitude > 4°), the exact same celestial body at the same moment is not considered a hilal in Jakarta simply because it is below the horizon and invisible. This contradiction challenges both common sense and academic reasoning. It highlights the complexity of celestial calculations in determining the lunar calendar and visibility criteria across different locations.

Figure-2 further emphasizes the inconsistency in lunar visibility determination. By 8:00 AM in Jakarta (illustrated by the brown figure), the hilal has grown significantly due to the increasing elongation: 0.5/hour × 14 hours = 7. It must be a lot larger than at sunset in Jakarta. At the exact same moment, in a location in the Americas, the Sun is setting, meaning Maghrib has just begun there. Because elongation is larger at that time, the hilal in the Americas should be at least 7° above the local horizon. The problem arises because the hilal in the Americas is recognized—since it is visible above the horizon—while the very same celestial body at the same second is not acknowledged in Jakarta, simply due to its invisibility. By 8:00 AM in Jakarta, the hilal is impossible to see because its brightness is overwhelmed by sunlight. This contradiction highlights a critical issue: lunar phases grow continuously regardless of location, and visibility alone should not determine recognition. The difference in local horizon perspectives challenges conventional methods of determining the hilal. It raises questions about how different locations interpret the lunar calendar and whether adjustments are needed for global consistency.

The above explanation highlights an important point: the altitude of the hilal (new crescent moon) is not a relevant measure to determine whether it is physically large. The hilal continues to grow regardless of whether it is above or below the horizon. Even if its altitude is negative at Maghrib, the new lunar month remains valid because the Moon’s phase progresses naturally. This also clarifies why the hilal in the western regions of Earth always appears higher than in the east. The reason is solely due to elongation increasing over time. As the hours pass after Maghrib, elongation continues to expand, making the hilal more prominent in locations further west. This insight challenges traditional approaches that rely heavily on visibility alone and support the argument that lunar phase continuity should be considered globally rather than locally.